You know what I haven’t had since…March 1996? A massage. You know what I’ve been promising myself I’d get just as soon as the pace slowed just a tad? I finally did it, the day before Mother’s Day. My present to myself.

And it was, well, have you ever had a bad massage? I guess it’s possible — you wouldn’t get me to try rolfing or anything — but it’s sort of like what Woody Allen said about orgasms: Every one was right on the money. Not that I’ve had all that many, but a good one can almost make me gibber incoherently. Once I was sitting in a salon with my hair in foil wrappers, gettin’ the lights turned on y’know, and a guy came around and asked if I’d like a free hand massage. I’m sure he was selling the miracle cream he used to do it, but I said yes and simply couldn’t keep up with his small talk, because my head was nearly lolling with pleasure. It was sort of embarrassing.

Anyway, I bravely opted for a masseur (the boy kind) and he was very respectful, but what else would you expect? Anyway, I’ve decided that if a boob slips out here or there, he’s seen a million others. He said my back was a mass of knots. I could have told him that.

How was your weekend? It was a pleasant M-day, and Kate and I went to the art museum to see the Diego-and-Frida exhibit, which was pretty great, but overcrowded. I was delighted by the large-scale sketches of the Rivera murals, as well as the Kahlo paintings, which were smaller and more powerful than I expected. I can’t imagine what it must have been inside a marriage of two talents like that, but they certainly made some great art in Detroit.

Some good bloggage this weekend, so without further blabbing:

The president visited the 50th state this weekend, and it happens to be one that loathes him. (South Dakota.) Nevertheless, this happened:

Most in the crowd, which was now three or four people deep, were die-hard Republicans and had little love for this president. “I wonder if he’s a Christian sometimes,” said Kristi Maas, 47, who owns a small hair salon in town. Just the thought was “scary” to her, she said. “He wants to take prayer out of everything. . . . Isn’t this country supposed to be based on religion?” Heads nodded around her.

…The crowd drifted slowly away. As she walked back to her car with her sister, Maas was already reconsidering her opinion of the man who minutes earlier she had believed maybe wasn’t a Christian — the man she worried was ruining the country.

… When Obama was done, the bar erupted in applause. A woman sitting in the smoking room by the video poker machines had begun crying.

“Most of the time I could care less what he’s talking about,” said Jason Hollatz, 37-year-old farmer. “Are all Obama’s speeches like that?”

A good read. You wonder what this country might be like without the propaganda factories making bank off people in South Dakota.

My husband has a thing for smart women in glasses, and I think he loves Tina Fey most of all. Here’s one reason.

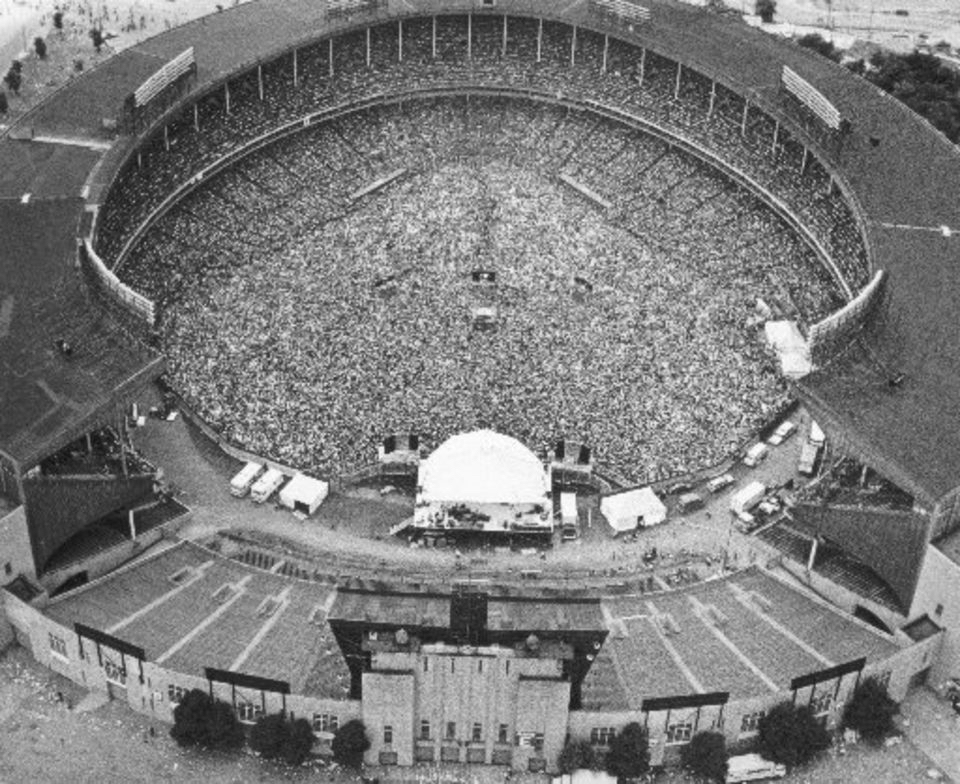

Finally, a picture I took at the state capital on Friday. Remember when we were kids, and our parents might take a roll or two of photos of us over the course of maybe a year? Now it’s a roll a day.

Oh, one final note: We watched “Welcome to Me” on iTunes, which wasn’t great but was a long way from terrible — a comedy in which Kristin Wiig plays a woman who wins the lottery and uses the money to launch her own vanity talk show called guess-what. It might be the ultimate commentary on Selfie Nation. Maybe one of the kids in that picture will grow up to do the same.

Happy week ahead, all!