Well, that was a nice trip, except for the ending — a five-hour flight delay out of Newark, with the five hours (closer to six-seven because I’m an early arriver) spent at the Newark airport. Now the real slog of the long winter begins. I’ll be spending it mostly in more-or-less isolation, as I feel I’ve been taking too many Covid chances and need to atone.

If I escape getting it from this trip, it’ll say something about the efficacy of vaccines, because I took chances. Masked on the flight, but not in the airport, unless it was crowded. Masked on subway trains, but not in subway stations; my rule was, if I can feel air moving across my face, it’s OK to take it off. Outdoors, not at all, indoors, depended on the venue. This, I recognize, is a little like sometimes wearing a condom, but oh well. Something’s gonna get all of us, and you gotta live your life.

But it was still a very nice trip. Ate good food, saw lots of great entertainment, actually got to a Broadway show (“Between Riverside and Crazy,” which was Just Meh). Took some pictures:

That’s the Bleecker Street subway station, built at a time when a little beauty in a public place wasn’t considered a waste of taxpayer money.

Chinatown fish market:

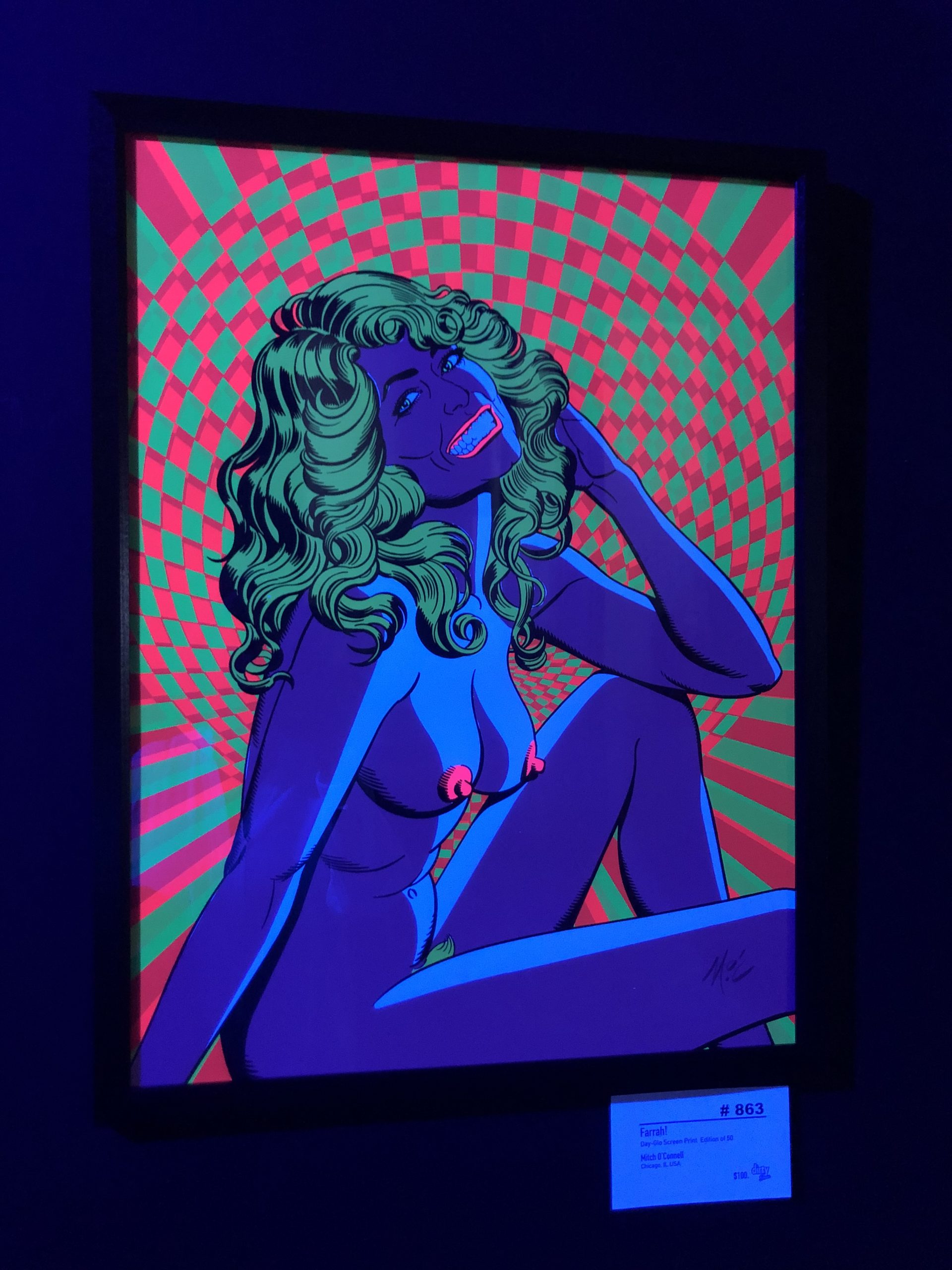

Beautiful ceramic of a gruesome scene, at an upper east side commercial art show.

At the same show, a depiction of my state, late-ish 18th century:

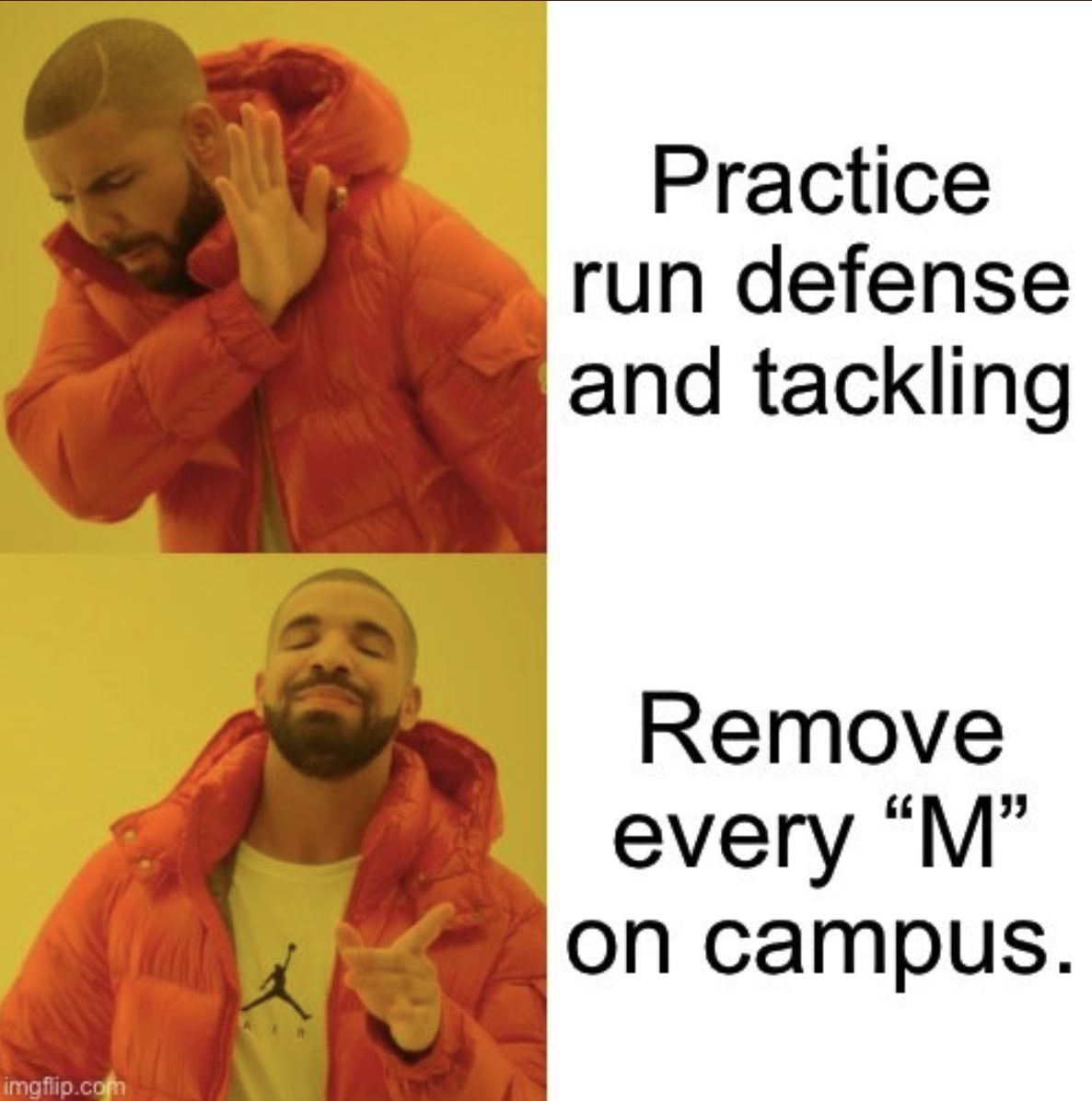

Brooklyn:

(I think the proper reading of that is, “I fucking love New York.”)

Jazz at the Blue Note:

Now I’m ready to economize and get back to dry January. Nothing like spending $18 for a mediocre glass of wine to make you ready to clip coupons and switch to Diet Coke.