The Columbus Dispatch was sold today. At times like this I am reminded of the words of the great Carl Hiaasen, in his novel “Basket Case.” Ahem:

When a newspaper is purchased by a chain such as Maggad-Feist, the first order of business is to assure worried employees that their jobs are safe, and that no drastic changes are planned. The second order of business is to attack the paper’s payroll with a rusty cleaver, and start shoving people out the door.

Maggad-Feist was plainly a fictionalized Knight Ridder, and “Basket Case” is old enough now that merely being shoved out the door has a certain chivalry to it, as it usually came with at least some form of severance. Our commenting friend Adrianne was a victim of the Dispatch’s new owner; here’s her experience:

These jokers bought my old newspaper, promptly laid off me and two other news editors, plus the entire photo staff. Six months later, they laid off the entire copy desk and moved all those jobs to Austin, Texas, where harried young graduates try to write headlines and design pages for the 60-plus newspapers in the empire. Reporters at their newspapers have not had raises in seven years, and do not get any overtime, no matter what the cause. They are owned by a hedge fund determined to wring every last drop of profit from their newspapers before selling out – I give them two years, tops. I didn’t think a newspaper chain could be worse than Gannett. I was wrong.

I left the Dispatch long, long ago. I don’t regret it. I had to leave to find my voice, which was waiting for me somewhere in Indiana, along with my husband and a lot of good people. The Maggad-Feist chain paid me adequately but never well, and when it all came to an end I could at least say the place had given me a lot to write about. But I was too young and ignorant to appreciate the good things about the Dispatch, mainly how goddamn flush they were, with cash — the sports team traveled to Ohio State away games on a company plane, and we’re talking reporters, editors, columnists, photographers and probably more — but mostly people.

The people! Oh my god, in these days of outsourced copy editing, it’s almost hard to imagine. There were so many people on staff. There were six writers just in the women’s department, where I started. Four of us were general assignment and two were specialists (brides, fashion), and we filled maybe a page, page-and-a-half a day, plus a Sunday section. There was a full-time editor for this department, and we were back there with sports and, oh, let’s just take a walk through that fifth-floor newsroom, shall we? There were four or five on the Sunday magazine, which used a lot of freelancers, too. A couple-three who only had to put out one Sunday page or fill a section with wire copy. Sports was packed with bodies, beat writers for all the big OSU sports and for Cincinnati baseball. (Kirk, help me out here: Did we have FTEs for Cleveland teams?) Let’s walk through photo (at least six or eight full-time shooters, plus a couple guys coasting toward retirement who handled scheduling and record-keeping and some studio work, and a secretary) and out into the main newsroom. There was the public-affairs editor, who filled a hubcap-size ashtray every single day. He was flanked by another chain smoker who edited the Accent front page — the features front, and only the features front — five days a week, and filled her own gigantic ashtray.

City desk? At least two editors on it at all times, frequently three. Reporters out the wazoo. Cops were covered 24 hours a day, lest mayhem break out overnight. There was a state desk, with just an editor in the newsroom, but plenty of writers who lived out in the circulation area and worked from home. And there was an art department, featuring actual artists. (One illustrated a lighthearted story about culture shock among the Japanese managers of the newly opened Honda plant. All the Japanese people in his drawings had buck teeth and thick glasses. Everything he knew about Asians he’d learned from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” apparently.)

And this is only the day crew. There was a slimmer but still robust night staff, including an overnight copy editor. He came in about the time I was leaving at 10 p.m., his skin the color of a fish that lives in the Marianas Trench. The guy sitting next to me watched him walk in, turned to me and said, “Creeeeeeak, and the coffin swings open for another night.” Plus there were people who had jobs I can’t fathom existing today. We had a copy boy, long after computers had replaced glue pots. He delivered papers to each desk as they came off the press and did miscellaneous other duties; maybe he washed the publisher’s car. There was a woman who kept the coffee urn filled and helped out in the basement test kitchen; yes, there was a test kitchen, a full-time food editor and full-time food writer. (Sample lead: “When I find myself out of ideas in the kitchen, I make muffins.”)

You might be getting the impression the paper was crappy. At that time, it most assuredly was. It later got better, a lot better. More on that in a bit, but a lot of this I now see was the result of a management that simply wouldn’t be brutal with people. They couldn’t be proactive about helping them improve, either, but I prefer it to cruelty. Alcoholics were tolerated, or helped through a full 28-day rehab, if they wanted it. For a time there was a copy editor who was blind. Seriously. A blind copy editor was a joke on some Mary Tyler Moore TV show, but we actually had one, a guy who leaned his white cane up against his desk. They could have booted him onto disability, but they didn’t. He edited the weather page, his nose pressed close to his monitor.

Half a dozen old men crafted editorials about Arbor Day and The Coming of Football Season and whatever conservative cause the publisher was on about. There were two — TWO — editorial cartoonists. I think that job has dwindled to about a dozen or so in the whole goddamn country.

I can see now this was a staff ripe for a management consultant to come in with a rusty cleaver, that we operated at near-Soviet levels of overstaffing, but honestly? Who cares. All those people collected their paychecks, cashed them and used the money to pay taxes, buy cars, raise families and otherwise keep the economy chugging along. If you think a belching factory smokestack is ugly, try one with nothing coming out at all.

The paper did get better, after I left. The deadwood aged out. A couple were broomed by the first halfway-decent, non-company man editor-in-chief the publisher hired; he’d already fired one in his previous job in Cincinnati. (A tart-tongued assistant city editor — we had a lot of those — said the victim needed to find his true employment destiny in a toll booth somewhere.) More smart editors did strategic hiring of good people, and little by little it was no longer the embarrassing paper in the state, but a pretty damn good one. Then the whole industry fell to pieces, and the last time I was there, they’d downsized the print paper to something about the size of a pamphlet. So sad.

Now it’s even worse, if you can imagine that. (I can. The one lesson the newspaper business pounded into my skull was to never say, “It can’t get any worse,” because it always, always can. And does.) I just heard a story today about a fine piece of newspaper watchdog journalism, and an editor’s dismissal of it, the next day: “No one read that thing on the web.” By this measure, Buzz Bissinger should get the Pulitzer for writing the Caitlyn Jenner story. I’m sure the newsroom was still a fun place to work during this renaissance, but it was also fun when I was sitting there on Saturday night, watching the clock and hoping I’d get out in time to enjoy a little bit of it, hoping the impossible drunk in charge wouldn’t get a wild hair up his butt and make me cold-call an address he’d just heard on the police scanner and ask why they were fighting so loudly that the police had been called.

I’ve worked at one other place with weirdos and characters like that: WGL, the AM station where Mark the Shark and I had our little radio show. I wrote about that place once already, but there are still more stories to tell. One of these days.

(A final note about typos here: A few of you have been correcting me, and I thank you. Autocorrect, in all my apps, is getting out of hand. I do this writing at night, mostly, and I’m tired and my eyes are tired and all the rest of it, but there’s a great deal of fucking autocorrect going on, too. Working on it.)

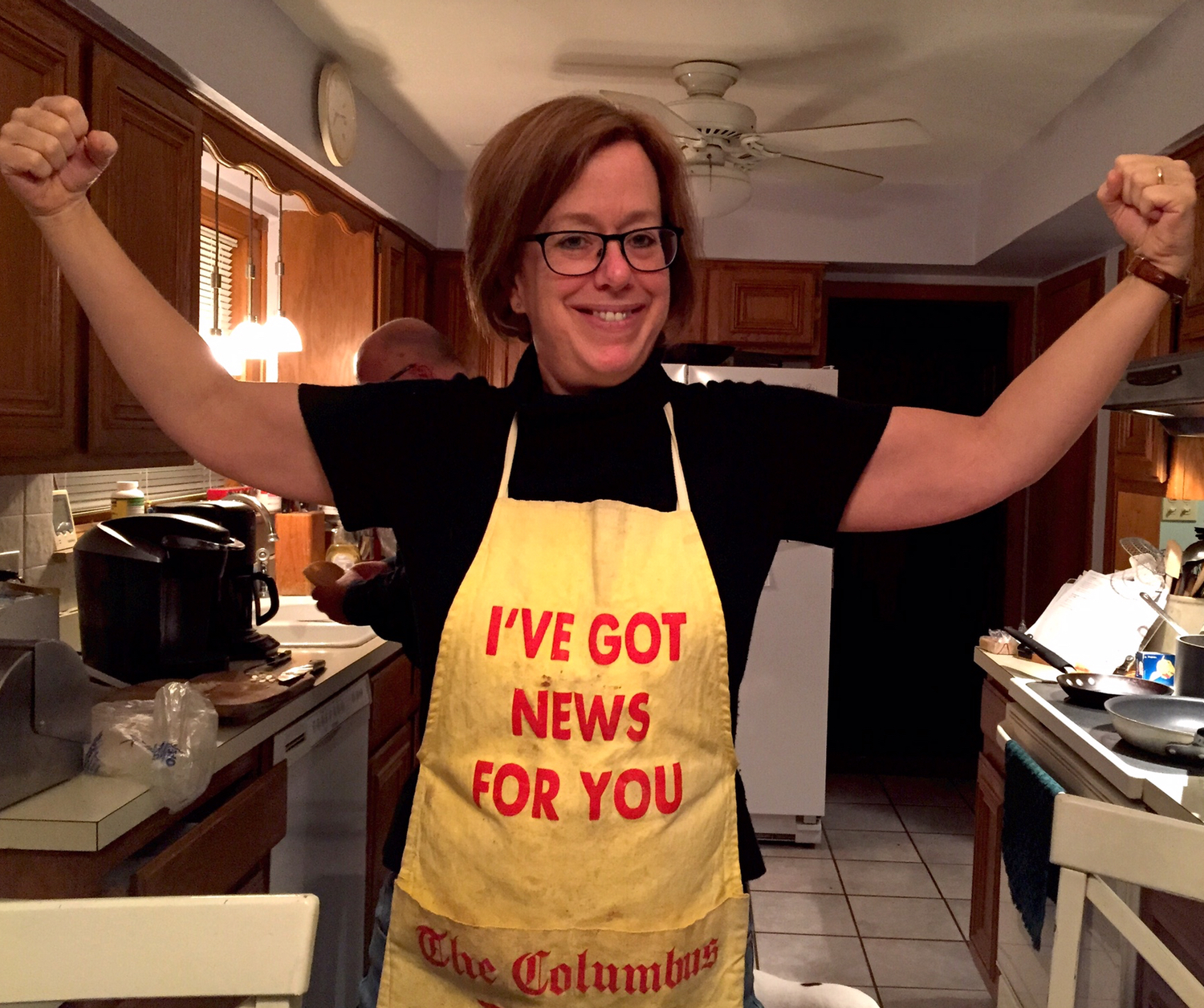

Finally, here’s one relic of the Dispatch I still have, and use often. Hashtags: #armwattle, #chinfat, #unflatteringphoto. This was something the photographers wore in the chemical-bath, pre-digital days, and I wear when I’m cooking anything splattery:

Happy Thursday, all.